RFK comes to Porcfest, members partake in the nude Olympics, a new secession bill is voted on in the House, board shakeups bring a new Executive Director: These are just a few big moments from this past year in the Free State Project. We check in a year later, in the 20th anniversary of the birth of the Free State Project, to see how much progress the libertarian migration has made.

Carla Gericke

How New Hampshire Became the Freest State in the Union | Guest: Carla Gericke | Ep 276

Sprouting from a graduate student’s thought experiment in 2001, over the last 20 years, the Free State Project has made a significant impact on the state of New Hampshire by gathering like-minded, liberty-loving folk who share a passion for freedom and independence. At this year’s New Hampshire Liberty Forum, Matt Kibbe sits down with Carla Gericke, president emeritus of the Free State Project, to discuss the history of the project, where it is today, and where it’s going in the future. In addition to making substantial legislative changes in the state, the Free Staters are also attracting the attention of major figures like Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Tulsi Gabbard, indicating that the real gains for liberty are yet to come. Subscribe to Kibbe on Liberty everywhere you get podcasts. The revolution is here. A movement of people free to live, work, and choose. We won’t tell you what to think, we just demand that you think for yourself.

This week we delve into rotten wife-beating cops, congressional war pigs, and other things wrong with Big Gov, like, idk, waving Ukrainian flags in the US Congress. On the other side of the equation, private charity efforts in Manchester include the Piscataquag River Park clean up this Saturday, also the Pine Tree Riot event hosted by AFP-NH in Goffstown (at the Kaloogians), and if YOU are looking for a small way to make a difference in Manchester, go pick up litter around your house! More about the park clean up from We <3 West.

Looks like April 18th is an auspicious date for me in the Free State!

From the pictures above, from left to right: Anti-lockdown “WE ARE ALL ESSENTIAL” protest in 2020 at the NH State House where I posed in my “TYRANNY RESPONSE TEAM” jacket with unknown patriots; a child to remind us, “Freedom over Fear”; honored as one of NH Magazine’s “Remarkable Women 2014” (in Sept that year, I won my landmark 1st Circuit “filming cops” case); and finally, a 2013 protest against militarized policing in Concord. (They eventually got their tank.)

May this post serve as a reminder that YOUR HUMAN ACTION CAN MAKE A DIFFERENCE.

Step one: Move to the libertarian homeland.

The US government sows fear. Its intelligence agencies sow paranoia. Politicians exploit both to stay in office. The Deep State feeds off this dark energy to grow.

Manufactured fear is running–and ruining–the world.

One prevailing geopolitical theory is “everyone is blackmailing someone”.

I have questions:

1. What are ppl doing in their everyday lives that is so grossly heinous? Might want to reflect on that and reform your ways?

2. With the advent of “deep fakes” the “blackmail model” of statecraft will soon be rendered obsolete, or at least lose much of its power to plausible deniability, which is where shady players are going to make their AI-generated bread & butter.

If “perception is reality” but we have evolved to a point where you cannot “believe your own eyes,” what have we wrought?

Living through the past few years persuaded me this confusion is not accidental.

Control Freaks are turning our streets and public spaces into insane asylums by making up shit on the internet and scaring people into literal MINDLESSNESS. Brain-dead zombies unable to discern truth from bullshit.

Where do we go from here?

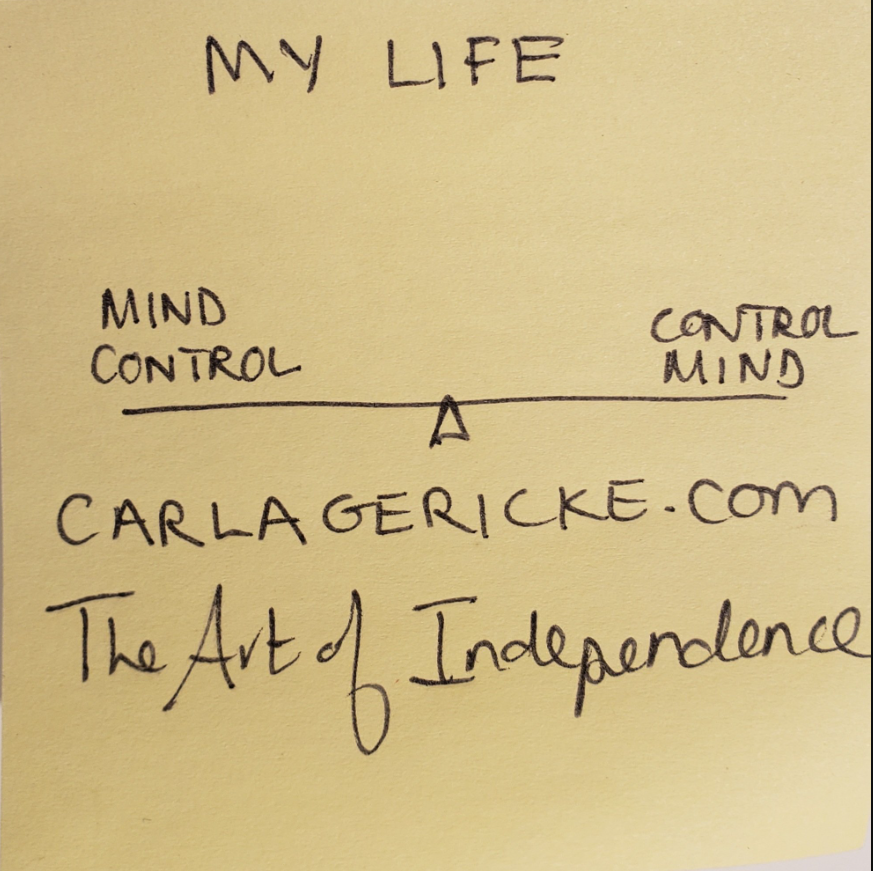

Get HEALTHY so YOU can control your own mind!

Control mind > Mind control

Will NH Senators Defend the Guard or Cave to The Military-Industrial Complex? (Manch Talk 04/17/24)

Tammy is back after a vacation in FL. Carla gets to tell her about the NHGOP Annual Meeting where several Republicans had their cars keyed by The Unhinged. We discuss the silly and sublime proposals and resolutions, and why geoengineering is now, at least symbolically, banned in the Free State.